29.04.25 - Innovative Design Research Internship Program (DRIP) entering its fourth season

In the summer of 2021, when pandemic restrictions had most people working and studying remotely, Professor Pina Petricone began experimenting with a new model of experiential learning, putting together an intensive internship for 12 undergraduate students that departed from the traditional internship model.

Taking full advantage of the multidisciplinary nature of the Faculty’s BAAS program, her format replaced the usual pursuit of “practical experience” in a design office with one that encouraged students to contribute to and advance design research initiatives in everyday practice.

One year later, this pilot course led to the official launch of the Design Research Internship Program (DRIP) in May of 2022, when Petricone invited 13 partnering practitioners to select one or two interns to undertake a defined design-research project over six weeks.

Last summer, the program saw its biggest cohort to date, with some 30 internships offered by a host of top Canadian design firms.

As DRIP 2025, which was available to all undergraduate Architectural Studies and Visual Studies students who had completed one credit of ARC courses at the 300 level, prepares to kick off, Petricone reflected on the first three years of the unique initiative, including the recipe for DRIP’s rapid success and also what comes next.

You have often talked about how the unique shape of DRIP is only possible within the rigorous context of Daniels’ BA in Architectural Studies program. What sets the Faculty’s DRIP program apart from other internships?

Unique across Canada, the pedagogical positioning of our BAAS program, which is firmly rooted in the liberal arts milieu, is what allows DRIP to define models of design research that advance lessons from design studios and course work into multivalent and sometimes interdisciplinary design research problems.

Combined with the opportunity afforded by the concentration of some of the country’s most recognized design practitioners at the University of Toronto’s doorstep, DRIP finds itself in a new category within the long history of design internships.

As an academic internship, DRIP moves freely beyond the mandate of “practical experience” or “readiness for the profession” of most architecture internships. At once unburdened by pre-professional obligations, DRIP exposes Daniels undergraduate students to architectural design as a form of research and in turn exposes the rich community of professional design practitioners to the unique talents of our students.

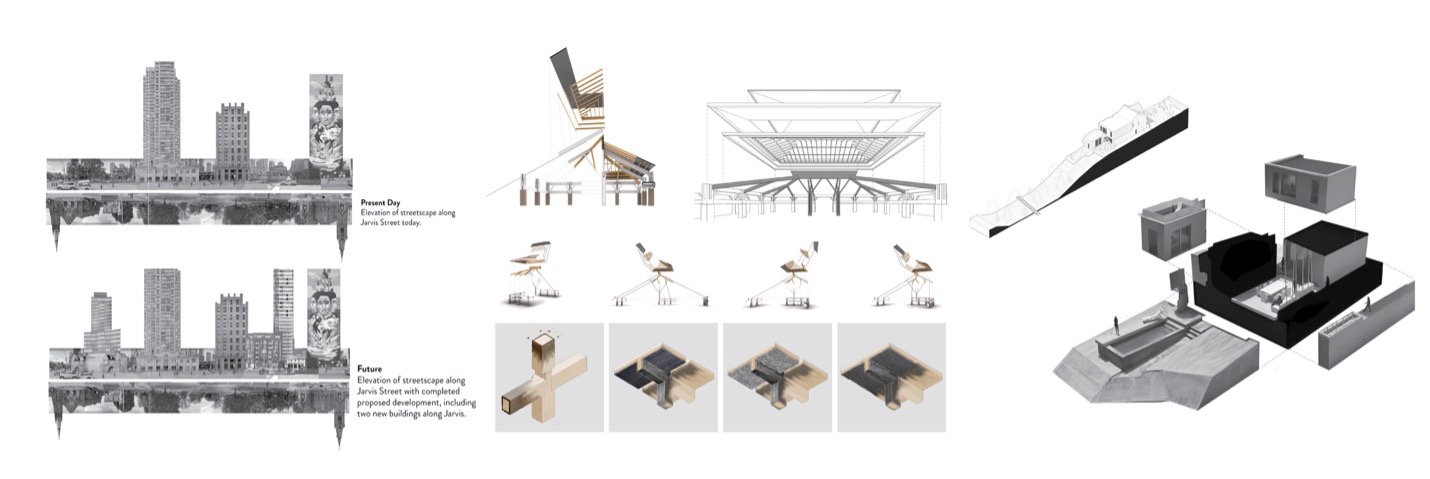

Left: ERA Architects DRIP intern Thea Freer analyzed and documented the historical, present-day and future attributes of Allan Gardens in Toronto. Middle: WZMH DRIP intern Alyssa Tao created a resource for the firm’s approach to building with timber. Right: Denegri Bessai DRIP intern Kaede Sato developed model-making techniques that tested spatial arrangements in ongoing residential projects.

DRIP understands that design research is an integral part of professional practice. Student interns tap into this activity and contribute to advancing applied research projects defined by their host firms. What range of research and findings have emerged in these first years of DRIP delivery?

It has been super-interesting to trace the patterns of research projects undertaken by DRIP interns in these first three years. Each internship relies on a practitioner-defined design-research project, born from exigencies of firm-specific past, present and/or future professional projects. The list of partnering firms is curated for diversity of practice models and value-driven enterprise, and no two projects are alike.

Both prospective interns and partnering practitioners declare their DRIP areas of practice, such as Urbanism, Landscape, Building Tectonics, Building Details, Public Space, Infrastructure, Digital Fabrication, Heritage, Energy Performance, Interdisciplinary, Housing, Public Policy, Community Engagement, Exhibition, Publication, etc., as well as their DRIP research methods, such as Conceptual Drawing, Mapping, Model Making, Technical Drawing, Archival Research, Historical Research, Photo Documentation, Rendering, Computation, Diagramming, Fieldwork or Spatial Analysis.

Common areas of focus, however, still lead to a wide range of research questions and outcomes.

Using various research methods in a number of practice areas, some of the prevalent design research that has emerged in DRIP’s first three years includes Typological Diagramming, Archival Documentation, Envelope Performance, Site Analysis, Critical Cataloguing, Proof of Concept by Modeling, Historical Tracing, Iterative Tracing by Rendering and Testing Tools such as comparing AI Platforms to advance digital practices in the design and documentation phases.

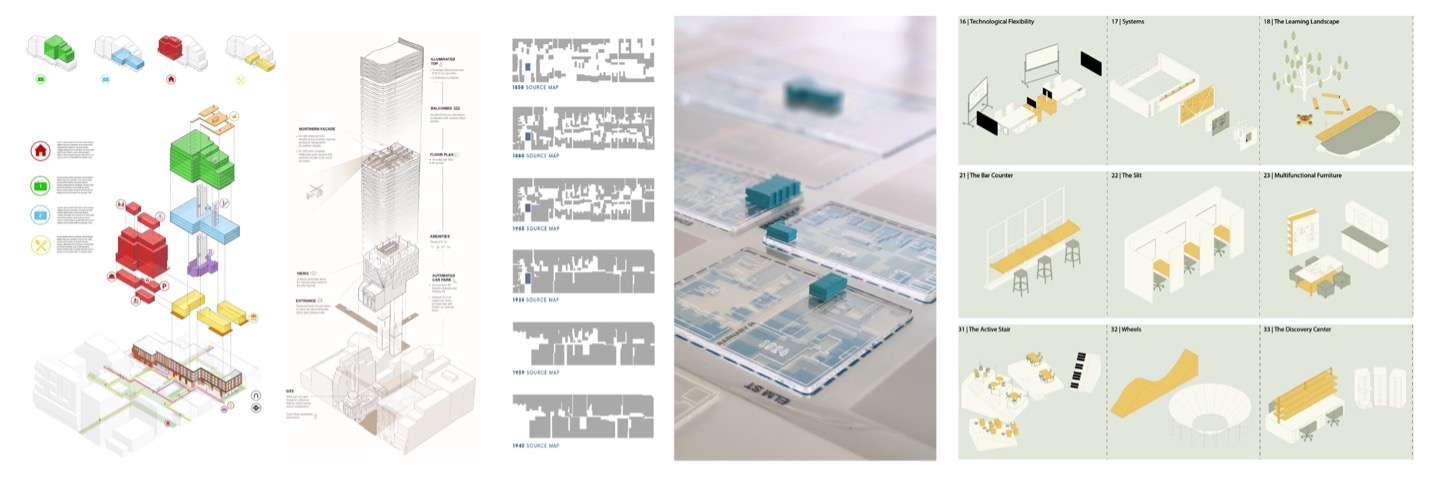

Left: Hariri Pontarini Architects DRIP intern Luca Patrick created a comparative archive that explores the unifying function of the exploded axonometric across several building types. Middle: ERA Architects DRIP intern Camilla Hoang traced lost heritage of seven 19th-century Black churches in Toronto via an interactive site model. Right: ZAS Architects DRIP intern John Wu created a catalogue of effective learning spaces for the firm’s innovative educational projects.

Your ambitions to evolve and refine DRIP as a far-reaching experiential learning model are already underway. Now that it’s entering its fourth year, what do you imagine for DRIP’s future?

I believe one of the greatest assets of DRIP is how the program embraces the opportunity to educate senior BAAS students not only with academic and technical skills but also with an understanding of the broader societal impact of their work. Our students and partnering practitioners are passionate about doing meaningful work and we are making strides to build-in a diversity of practice best matched with a diversity of students in all streams of our undergraduate program.

A big part of this is slowly but surely increase engagement of interdisciplinary design practitioners and active agencies to partner with us and expand our roster to in turn invite their own collaborators to inform not only the DRIP experience but also the research project. Critical to this growth is directed feedback each year from both students and partnering practitioners, which has proved invaluable to the development of DRIP as a more far-reaching program and we’re working on two specific fronts.

We are now exploring DRIP grouped initiatives where the strengths and interests of graduating students are assembled to work with a partnering practitioner that invites a collaborator(s) to amplify the six-week project. This is a great opportunity for out-of-province or out-of-country practitioners to engage in DRIP without the impairing logistics of students having to travel.

At the same time, we are investigating how we might engage international partnering practitioners via our international (and national) students that might be already relocating for the summer. I’m excited by the possibilities!

This year’s DRIP begins on May 5 and runs until June 16.

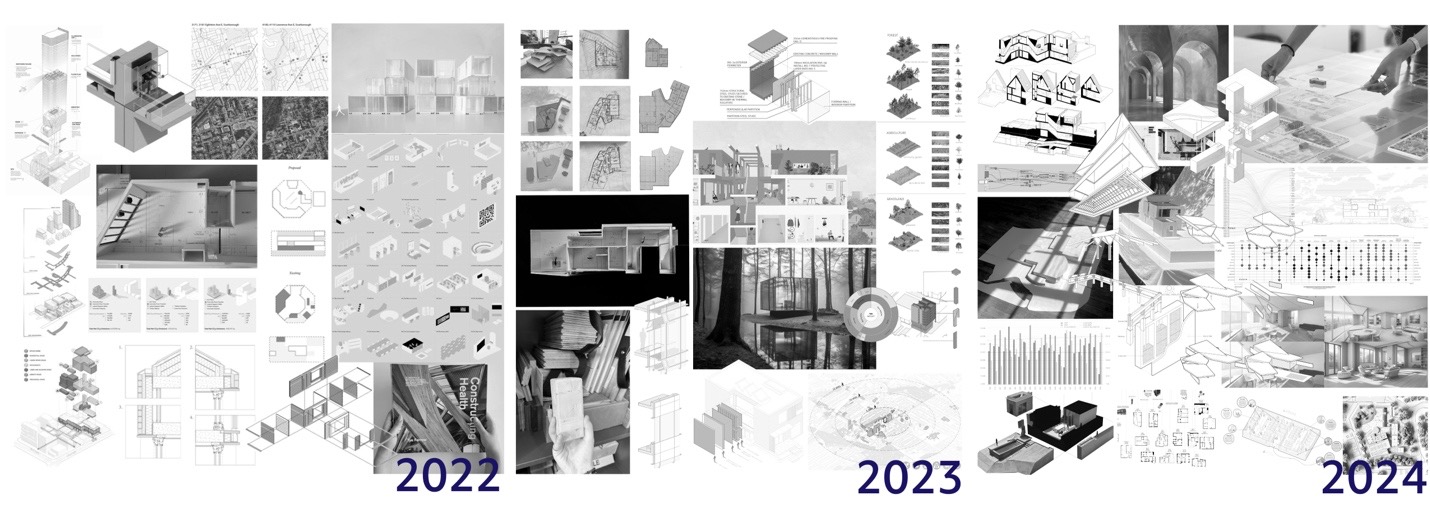

Banner image: Collage of work produced by DRIP students during each of the program’s first three years.

Homepage image: Collage of DRIP pilot work led by Pina Petricone at her design practice, Giannone Petricone Architects, with 12 BAAS students in 2021.