28.02.17 - Q&A: cheyanne turions (MVS 2016)

cheyanne turions (MVS 2016) had already established a name for herself as a curator before beginning her Masters of Visual Studies in Curatorial Studies at the Daniels Faculty. With exhibitions in artist-run centres and arts organizations across Canada — including Art Metropole in Toronto, the Western Front in Vancouver, and SBC Gallery in Montréal — her work has been recognized as “highly considered and articulated” as well as “relevant, provocative, risky, and ambitious.” In 2015, she received the Award for Emerging Curator of Contemporary Canadian Art from the Hnatyshyn Foundation and TD Band Group, and the Reesa Greenberg Curatorial Studies Award. Honours Bachelor of Arts in Architectural Studies student Josie Northern Harrison (HBA 2017) caught up with turions to learn about her most recent role as Artistic Director for Trinity Square Video, the experiences she gained while studying at the Daniels Faculty, and the role of art and artists in “working toward a decolonized, Indigenized future.”

You completed your Bachelors Degree in Philosophy at UBC. What inspired you to depart from this field and pursue a Master of Visual Studies in Curatorial Studies at U of T?

When I was in school at UBC, I was lucky enough to have a Young Canada Works position over the summer at an artist-run centre called Cineworks. When their Programs Manager left, they invited me to apply for that position, so I ended up working there after I graduated as their Programs Manager and Curator. Art was a way for me to practice philosophy. I could put forward a hypothesis about the world, and the exhibition could test whether the hypothesis meant anything to other people.

I moved to Toronto in 2010, worked here for a couple years, and developed a lot of respect for Barbara Fischer (the Director of the Daniels Faculty’s Master of Visual Studies program in Curatorial Studies). The Daniels Faculty later brought in Charles Stankievech as the Director of the Visual Studies Program, who is also someone that I respect. Through conversations with Barbara and Charles, I realized that the MVS program could be a place for me to continue developing my skills and study with people whose work I admire.

How did your understanding of curation change over the course of the program at U of T?

At the end of the Masters program, you are responsible for producing an exhibition and a complementary writing component. For the exhibition, students in the program partner with one of the university galleries. I had previously worked primarily in an artist-run culture, and this was the first time that I had worked in such a robust bureaucracy. One of the skills I gained was how to negotiate working within much larger institutions.

And university galleries play a different role in the arts community than regular galleries, don’t they?

At university galleries, the connections between exhibitions and knowledge production are more explicit, which you can see through the publishing program at the Art Museum. You can also see the connection between exhibitions and the student body. The Art Museum invites MVS students in to develop exhibitions that are ultimately presented parallel to those that the Art Museum develops as an institution. Because university galleries have rather stable funding, I feel they have an obligation to be radical and experimental with the types of exhibitions that they produce. We’re pretty lucky in Canada to have an art world that’s not intrinsically tied to the art market; we can ask different questions and produce different types of shows.

In your article “Decolonization, Reconciliation, and the Extra-Rational Potential of the Arts” written for ArtsEverywhere, you describe art as a method of “working toward a decolonized, Indigenized future other than through state sponsored and articulated processes of reconciliation.” Could you expand on this? In what ways can art contribute to decolonization?

Art allows us to have strange ideas. It’s a place where propositions can be made that can’t be made in politics or science. It’s a place where we can think differently. The Truth and Reconciliation Report (TRC) was published on behalf of the Canadian State. It was not an Indigenous-led process, and it is, we can generally say, a process that has been developed to ease of the mind of settler Canadians rather than address the trauma that is anchored in Indigenous communities. Art is a place where we can imagine a decolonized future not authored by the Canadian State, and it is important to hold the idea of decolonization in our minds going forward.

Why is it important for artists to take on this role?

If you are doing work or producing scholarship in Canada then you should be engaging with the political realities of this place. The production of art and the making of exhibitions is not neutral. It is important to realize how we perpetuate power relations in our work, and if you think there is something troubling about the way power is distributed in civic society then you should be doing something to counteract that.

What inspired your work in this area?

I grew up in northern Alberta on a farm, where there were a number of reserves close by, and my mom is of Ojibwe heritage. I have always thought a lot about what it means to be of mixed settler and Indigenous heritage. I don’t know how to look at culture in this country and not think about the ways that settler colonialism has impacted upon it.

You are the Director of No Reading After the Internet – a reading group for cultural texts. Could you describe the experience of reading an article aloud to a group? What are the outcomes of this activity?

No Reading After the Internet is an event where we read a cultural text aloud together. There are a couple reasons why it’s structured this way. The first is that it removes a barrier of entry. All you have to do is show up, and we encounter the text together. The other thing is that when people use their voice to read a text out loud, they are more apt to participate in the conversation that follows. One measure of success is whether everyone who came to an event spoke about the text. The nice thing about No Reading is that it de-emphasizes scholarship. We’re all encountering this text for the first time together. It’s much more improvisational than a class at school. It’s not about performing how smart you are; it’s about being curious, and being willing to think with other people. The conversations that come out of this process have been incredibly rich.

In July 2016, you were appointed the interim Artistic Director of Trinity Square Video (TSV). How has TSV contributed to the arts community in Toronto? What has been your vision going into this role?

Trinity Square has been around for over 45 years; it’s one of the oldest media arts, artist-run centres in the country. Its areas of activity revolve around production and presentation. For the creation of the work itself, we have production gear and post-production resources that our members can access. For the presentation of the work, we make exhibitions, coordinate screenings, host talks, and make publications. The production and presentation activities at Trinity Square are closely linked; there is reflexivity between the activities so that they inform one another.

John G. Hampton (MVS 2014), who was also a graduate of the MVS program, was at Trinity Square prior to me. I’m still in the process of realizing the exhibitions that he had put together. Going forward, I’ve been thinking about what it would mean to divest from white supremacy. Is there some way as an institution or as a structure that we can interrupt white supremacy through our work? I feel like the answer has to be yes, but I don’t know how exactly to do that yet, so I’m going to try and figure that out.

Do you have any advice for undergraduates pursuing a degree in Visual Studies from U of T?

I know art students are often encouraged to apply to open calls as a way to get their work seen. I would say that a better way to do this is to ask curators to do studio visits with you. As a curator, a studio visit is the basic unit of research. It is the equivalent to laboratory tests if you’re a scientist. So I would say find a curator that you respect, and ask them to come view your work and give you feedback.

What advice would you offer those considering the Master of Visual Studies in Curatorial Studies program?

Be as curious as possible. Go to as many shows as possible. Just writing a few sentences about every show you see to reflect on what you’ve seen and how you’re interpreting it is an incredible way to be critically present.

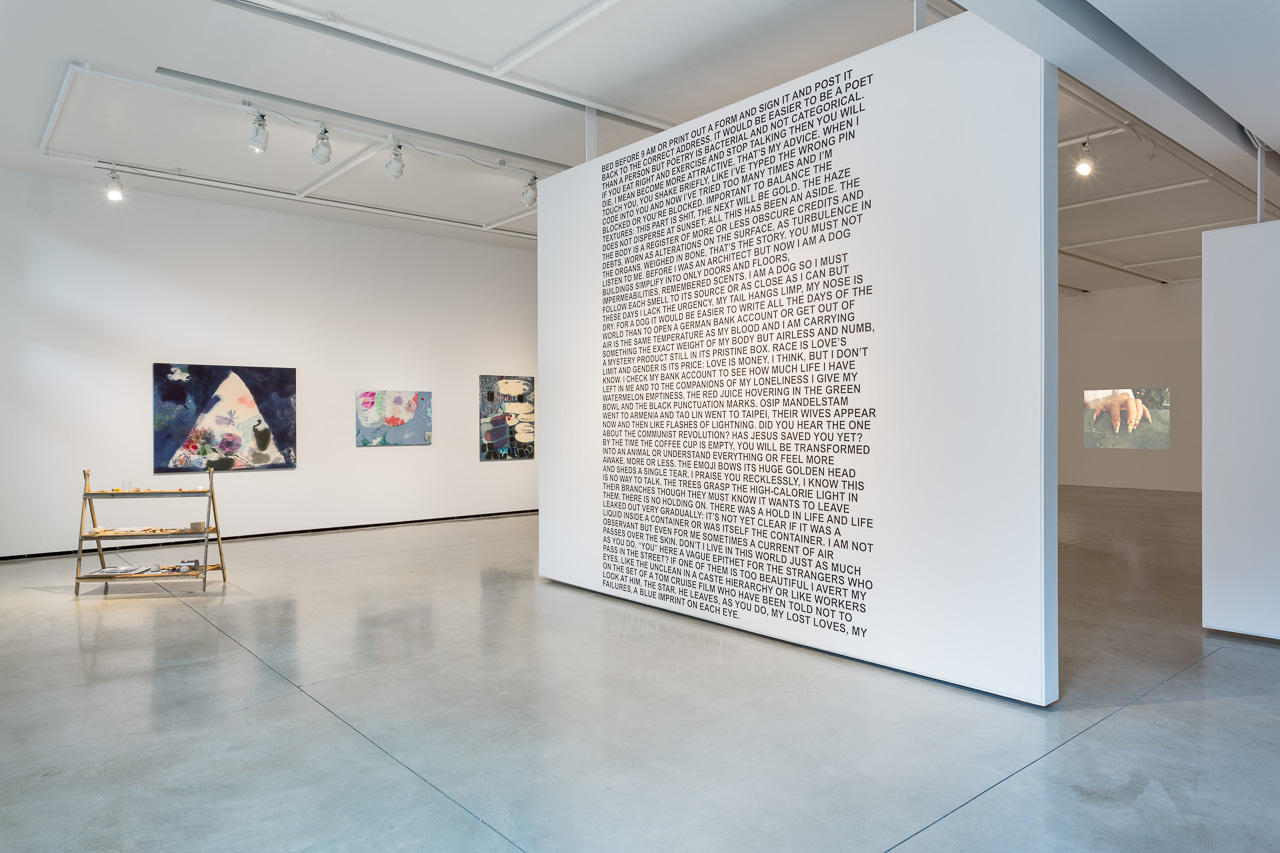

Photo, top: Image of exhibition The Fraud that Goes Under the Name of Love at the Audain Gallery. Photo by Blaine Campbell.