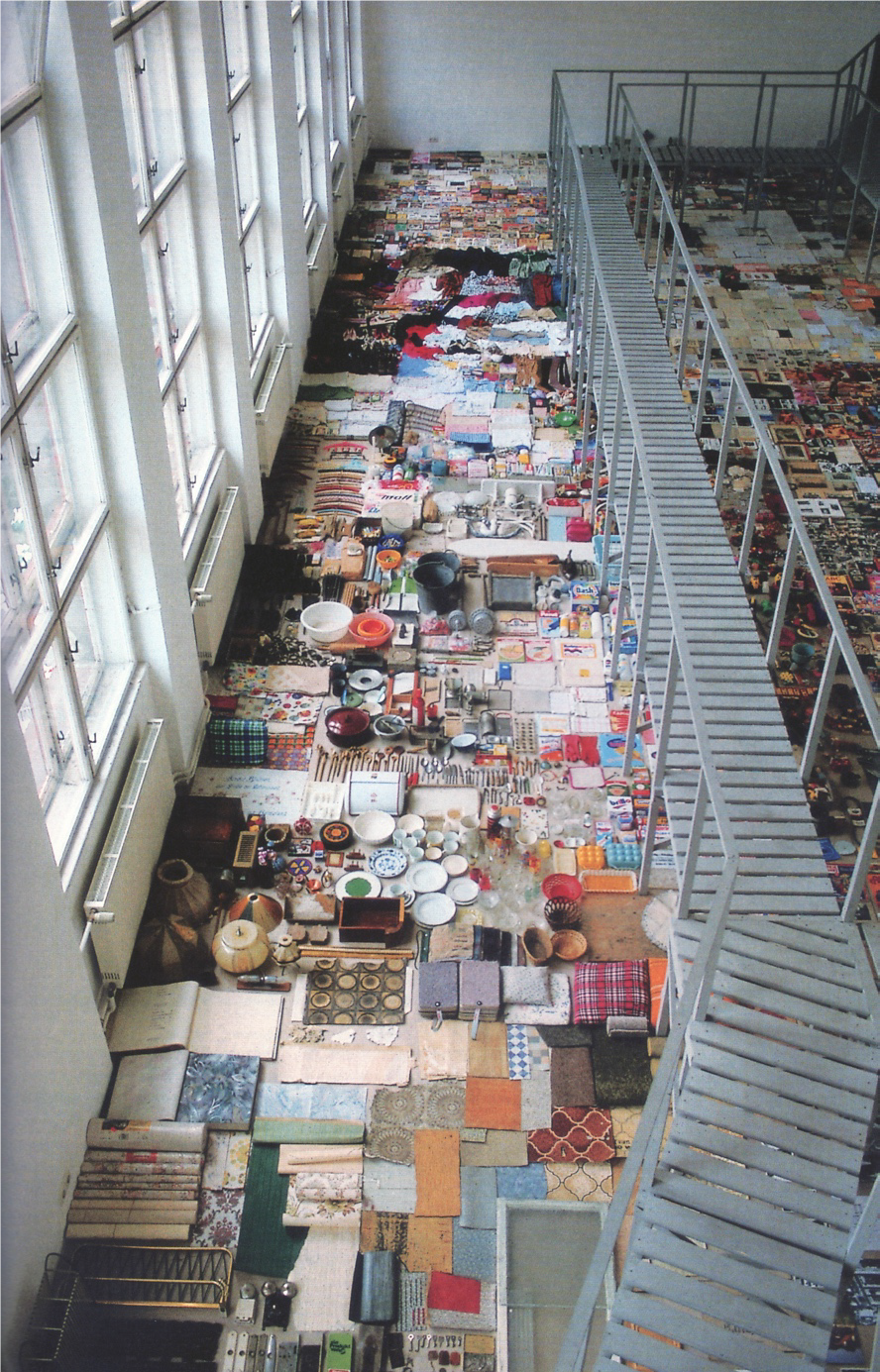

STUFF

Karsten Bott, One of Each

ARC3016Y S

Instructor: Laura Miller

Meeting Section: L0103

Tuesday, 2:00pm - 6:00pm; Friday, 2:00pm - 6:00pm

“At the very least, I hope to have convinced you that, if our challenge is to be met, it will not be met by considering artifacts as things. They deserve better. They deserve to be housed in our intellectual culture [and in our architectural constructions] as full-fledged social actors.

They mediate our actions? No, they are us.”

–– Bruno Latour On Technical Mediation –– Philosophy, Sociology, Genealogy

The central question this research studio will explore is how architecture can operate with greater generosity, inventiveness, and reciprocity in calibrating object - human relationships in the spaces we construct. How do we share the physical spaces we inhabit with the myriad of objects we acquire, use, store, and accumulate over time? How do these artifacts in turn shape the architecture of our lives? How do the objects we encounter prompt us to assume different roles – user, consumer, viewer, owner? From familiar belongings found within the home, to the jarring mix of impersonal furnishings and personal records amassed within institutions such as schools or hospitals, to the valuable or irreplaceable objects displayed and sequestered in our museums and galleries, to the excess belongings crated, preserved and often forgotten in our self-storage sites or institutional archives, our environment is populated by stuff. We are stuffed by stuff, you might say.

One legacy of modern architecture’s refusal of mass in favour of structural expression and surface was to leave behind the handy device of poche and all that it could potentially contain – poche is related to pocket, after all. Today’s exigencies of efficient and cost-effective construction frequently leave us with everyday spaces that are defined by the merest of boundaries: sheetrock on metal studs for example, partitioning spaces that can seem to barely contain us, not to mention our stuff.

It is no surprise that stuff, then, is often what ‘happens to’ an architectural space. Scenario: the photographer packs up after finishing a shoot, having captured a project’s intended image. Next, stuff deliberately kept out of the frame – the motley detritus of daily life, or the still-serviceable objects considered to be outside of the current parameters of taste – moves in. Clearly our stuff can make us uncomfortable, revealing too much, such that in certain spaces, stuff is edited out of the defacto intentional frame. In other contexts, it is only the explicit intentional frame that we are ever allowed – think of museums, where artifacts and people’s movements are scripted according to curatorial narratives, while vast quantities of collections are ‘disappeared’ in off-site locations. Stuff can cause discomfort in other ways as well; not by being ‘wrong’ but by being there at all, through its unrelenting, obstinate presence, or perhaps, by not ‘behaving’ properly. Witness the Marie Kondo phenomenon, a reflection of the cycles of anxiety and attachment that have become part of how we define ourselves through objects. Like clueless guests who have overstayed their welcome, ‘Kondoization’ thanks objects for being there, and then shoves them quickly out the door, or submits them to a regime of rolling, compaction, and obedience. Kondo has one part of her equation right: she recognizes the object’s presence, even if ultimately unwanted in the purged environments she prescribes.

Artifacts are not complacent ‘things’ at all, existing only to serve us as tools or to silently assist us in the definition of our own identities. Rather, objects are, together with humans, animals and other living organisms, active agents in shaping our mutual technological and cultural condition. This shared condition is evident in the double life architecture leads, first, as a series of cultural and technical (tectonic) artifacts, and second, in its operation as a means of mediation – in its framing of artifacts and other inhabitants it contains.

The STUFF research studio will investigate the ways that architecture can better engage in such framing. Binaries that divide objects and people into the ‘inanimate’ (stuff) and the ‘animate’ (us) do not recognize the potential of how human and ‘non-human’ actors, if considered together from the inception of the design process, could potentially inform the spaces we create in new ways. What if stuff was considered as important a ‘client’ as an individual or an institution? Would thinking this way change how or what we design?

This studio’s inquiries will be deliberately constructed across diverse scales of architectural and artifactual investigation, ranging from the intimate spaces of the home to institutional sites, (some singular, some generic), to storage spaces that are tectonically precise and geographically diffuse. The collection of scenes, sites, and landscapes listed below, where stuff resides according to different scenarios and durations, will be the starting point in the studio’s examination of how we engage and interact with material artifacts. Within each category there is additionally a range of possible scales of inquiry, depending on the individual interests that a student may bring to the studio.

- Domestic scenes (from furniture to the private house to multi-unit housing);

- Institutional sites (from the archive to the museum and other sites that collect, store and display physical artifacts; from corporations and government agencies that collect and store both physical material and data);

- Technical and Logistical landscapes (from self-storage facilities to shipping depots to data storage to refuse and recycling facilities).

For the first part of the term, the studio will engage in collective research. Each student will examine, analyze and document case studies selected from each category. This component of the studio’s research will allow students to become familiar with the options regarding possible scales, settings, kinds of artifacts implicated, and issues pertinent to their emerging thesis design inquiry. Ultimately, for thesis, a student may choose to work in one or more categories and/or scales.

A number of theoretical and historical readings and discussions will supplement this work, laying out significant ideas about the roles of the material artifact, its value, and its spatial disposition in different architectural contexts. We will also consult other publications, contemporary and historical, such as shelter magazines, organizational manuals, trade magazines, how-to manuals, etc.

In the first weeks of the studio, students will also develop a travel agenda to one of two proposed destinations: London, England or Boston/NE corridor, U.S. The travel will focus on a cross-section of institutional sites that include early collecting institutions, both academic and public; private collections such as house museums; and contemporary museums adapted to industrial sites. (Boston/NE Corridor: Dia Beacon; Mass MOCA; Peabody Museum, Harvard; Isabella Stuart Gardner Museum; Museum of Fine Arts; Sackler Museum, Harvard; Fogg Museum, Harvard; Institute of Contemporary Art /ICA; possibly also a side trip to Yale/New Haven, to see the Yale Center for British Art and the Yale University Art Gallery.) (London: Sir John Soane House & Museum; British Museum; Tate Britain; Tate Modern; Victoria and Albert Museum; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; National Design Museum; National Gallery.) During the term, we will arrange to visit storage sites in and around the GTA and, led by studio interests, other local sites.

Following our return from travel and for the remainder of the term, students will be asked to develop and present three possible scenarios for their thesis investigation, importantly, accounting for the material artifacts that will be produced in the course of thesis prep and thesis. How will the research be developed in a material form? These scenarios are a means to test students’ ideas about one particular kind of setting (i.e., domestic scene) or scale (i.e., furniture); to look at more than one setting as a means of comparing issues that are common to each (i.e., storage); or to propose to combine settings (i.e., self-storage and multi-unit housing).