Pablo Espinal Henao, "Delta Casting: Democratized Formwork Printing in Antioquia, Colombia"

When Pablo was considering topics for his undergraduate thesis project, his thoughts turned to Alta Vista — a mountainous area of Colombia, near the city of Medellin, where his grandfather once had a farm. School infrastructure in the area, Pablo recalled, was poor.

"The main problem stems from the fact that it's so far up, and the roads are so narrow," Pablo says. "Moving building equipment into these areas is really difficult. What that means is that you're not getting schools built far up the mountain, where a lot of the population is. And so people end up commuting down the mountain and coming back up. It's really inefficient."

Since traditional school-building methods weren't suited to the area's topography, Pablo began to wonder if it would be possible to produce better results with nontraditional methods. For his thesis project, he resolved to develop a way to use 3D printing to accelerate the process of school construction in Alta Vista.

A 3D printer, he theorized, could be used to create plastic formwork, which could then quickly be filled with concrete or another aggregate material, like cob.

The idea of using 3D printing in construction isn't a new one. Architects have already experimented with various ways of using 3D printers to build full-scale structures — but most of the existing methods require heavy equipment, like seven-axis robot arms or other large-scale printing systems, which would be difficult to transport up a mountain road. Another issue: the cost of equipment.

"This thesis project was about the democratization of a type of architecture," Pablo says. "In the technology stream at Daniels, we got to explore a lot of really insane uses of things like CNC mills and seven-axis robots to create very high-end projects. While this was interesting to me, I always wondered why the technology was never seen in lower-budget projects. I realized it was because most digital fabrication systems were really expensive."

In order to develop a method of 3D printing that would be affordable and lightweight enough to be deployable in Alta Vista, Pablo decided to investigate a technology that hadn't previously been used much in large-scale projects: delta 3D printing.

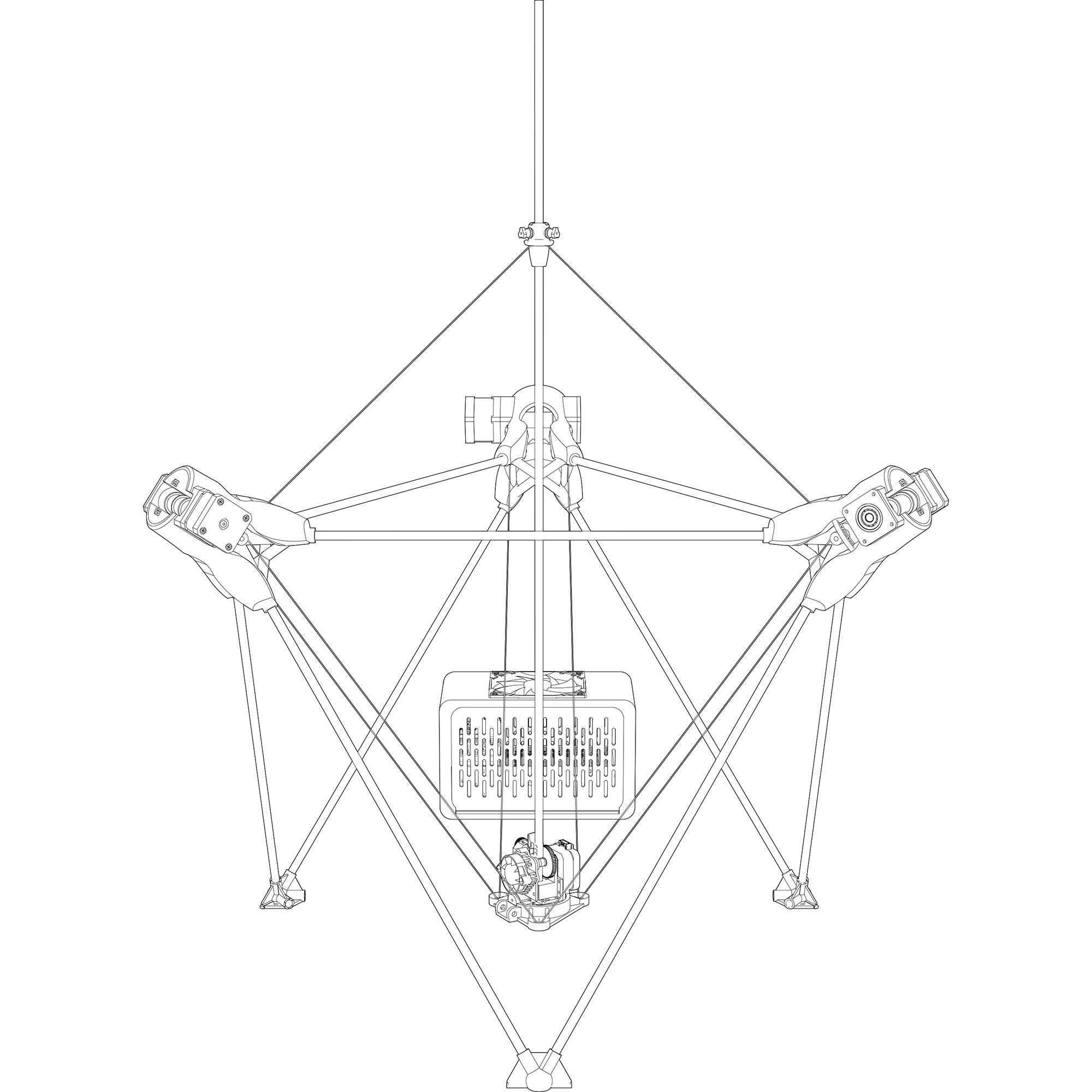

A delta 3D printer consists of a print head mounted on three arms. Unlike the more common cartesian method of 3D printing, in which the print head moves rigidly along three fixed axes, delta printing's tripod configuration allows the print head to move quickly in any direction. This speeds up the printing process.

There was another aspect of delta printing that appealed to Pablo: delta printers are typically less bulky than cartesian printers. After some research, he discovered a method, developed by a designer named Daren Schwenke, for building a delta printer out of tensioned cables, rather than rigid metal rods. This, Pablo concluded, would be perfect for Alta Vista. A cable-based delta printer could be made light and flexible enough to be packed into the back of a truck. Transporting such a device up a mountain road would be relatively easy. And the components for a cable-based delta printer — even a very large one — wouldn't be particularly expensive to obtain and assemble.

But there was a problem, and it was a significant one: no such machine existed. No manufacturer or hobbyist had ever tried to create a cable-based delta printer that could be used at architectural scale. If Pablo wanted to experiment with one, he was going to have to build one himself.

And so that's what he did.

Top: Pablo's delta 3D printer design. Bottom: A close-up of Pablo's motor head prototype.

Working under the guidance of his advisors, lecturer Nicholas Hoban and assistant professor Maria Yablonina, Pablo used Rhino and Autodesk Inventor to design and prototype a custom-built motor head that he could use to manipulate the tension and position of his 3D printer's cables.

Once he had designed the motor head to his satisfaction, he used a store-bought 3D printer to fabricate actual, working models of the heads. Using three of the heads, he was able to assemble a scale model of his delta 3D printer design — not large enough to print an actual building, but large enough to work as a proof-of-concept.

But the machine wasn't enough: Pablo also needed to create computer software that would take data from a computerized 3D model and translate it into instructions for the motor heads. In other words, the printer needed a brain.

For this piece of the project, Pablo taught himself how to use Arduino, a type of programmable microcontroller designed for use in the prototyping stages of engineering projects. Eventually, after some trial and error, he taught his printer how to think. His scale-model printer was now a working model.

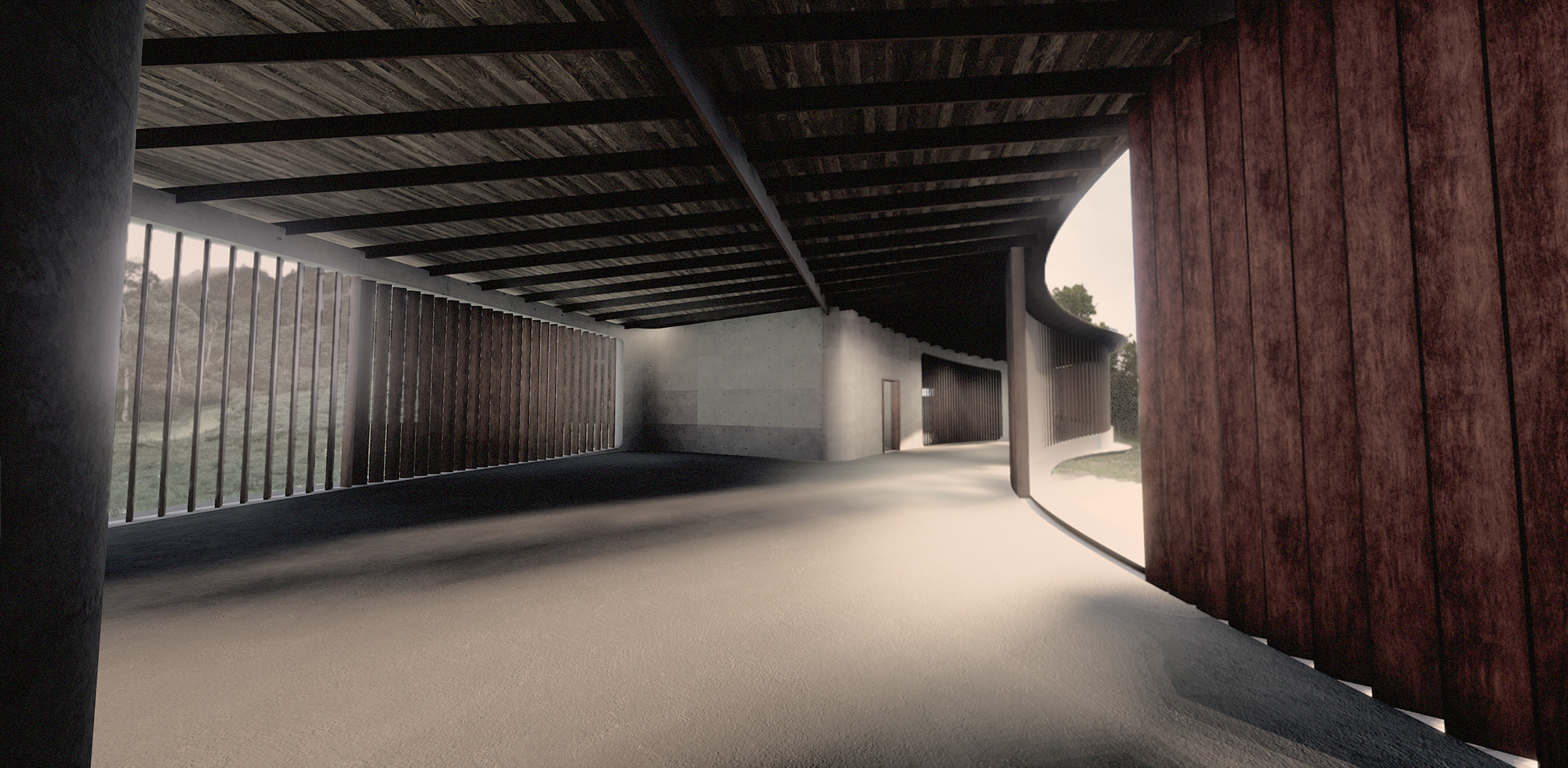

Rendering of Pablo's school design.

With his delta printer in good shape, Pablo turned his attention back to his site, in Alta Vista. He developed a proof-of-concept school design that takes advantage of the flexibility of 3D-printed plastic formwork to create walls with complex curves, which subtly alter the learning environment by creating private space within classrooms.

Pablo will be returning to the Daniels Faculty in fall 2020 to begin his Master of Architecture studies. He has received an Ontario Graduate Scholarship, which he'll use to continue his thesis research. He hopes to develop his printer to a point where it can be tested at full scale.