Social distancing is hard for architects. Studios and reviews are inherently social, and design work often requires the use of bulky tools — like 3D printers and laser cutters — that most students and practitioners don't have in their homes. With the University of Toronto in online-only mode for the foreseeable future, Daniels Faculty instructors and students have had to find ways of taking all that in-person creative energy and fitting it into the confines of their computer screens.

As always, the Daniels community has risen to the challenge.

For "The Pleasure of Ruins: The Allure of the Incomplete — Drawing as Thesis" (ARC3016), a graduate research studio with an associated thesis prep component, associate professor John Shnier took students on a trip to Rome, as he does every year. This year, as the group was preparing to head back to Toronto, there were news reports of a coronavirus outbreak in northern Italy. The group made it back safely, but soon afterward the university cancelled all in-person classes.

After some deliberation with his students, Shnier moved the studio's meetings and reviews to Blackboard, an online learning platform. Students now show their work using screen-sharing, and the class discusses the work using Blackboard's videoconferencing features. "We did an interim review two weeks ago," says Shnier. "We invited two guest reviewers, and it worked out to be pretty good."

Even before COVID-19, Shnier was a prolific Instagrammer of his students' work — but now, with in-person reviews suspended, he has redoubled his efforts to put student work online. His Instagram feed is currently full of videos made by students in response to some of the architectural inspiration they picked up during the Rome trip. (The ghostly, holographic effect is a result of Shnier's method of adding the videos to Instagram, which involves pointing his phone's camera at his computer monitor.)

This one is by Enica Deng:

And this one is by Steven Chen:

...

In assistant professor Adrian Phiffer's undergraduate course, "Reality and its Representation" (ARC465), some students have taken the shift to internet-based coursework into their own hands.

The course is heavily focused on readings. Before the pandemic, student groups would give presentations on their assigned readings in front of the class. Post-COVID, a different approach was required.

Students Thomas Buckland, Sara Ghorbanpour, Sam Shahsavani, Lucas Siemucha, Peter Dowhaniuk, and Stuart Thomson decided to create an Instagram account with videos of their reading presentations. That way, their classmates would be able to access the discussion from their home computers and respond in the comments on each Instagram post.

Here's one of the group's videos, featuring Lucas Siemucha and Thomas Buckland:

The use of Instagram dovetailed nicely with the week's readings, which were on the theme of "flatness" — the non-hierarchical, decentralized way information travels online. "Anyone with an interest can access and hear these presentations," Phiffer says. "I think there's a benefit to that. Plus, the students came up with, for lack of a better word, 'cool' ways of making the presentation, given the medium."

...

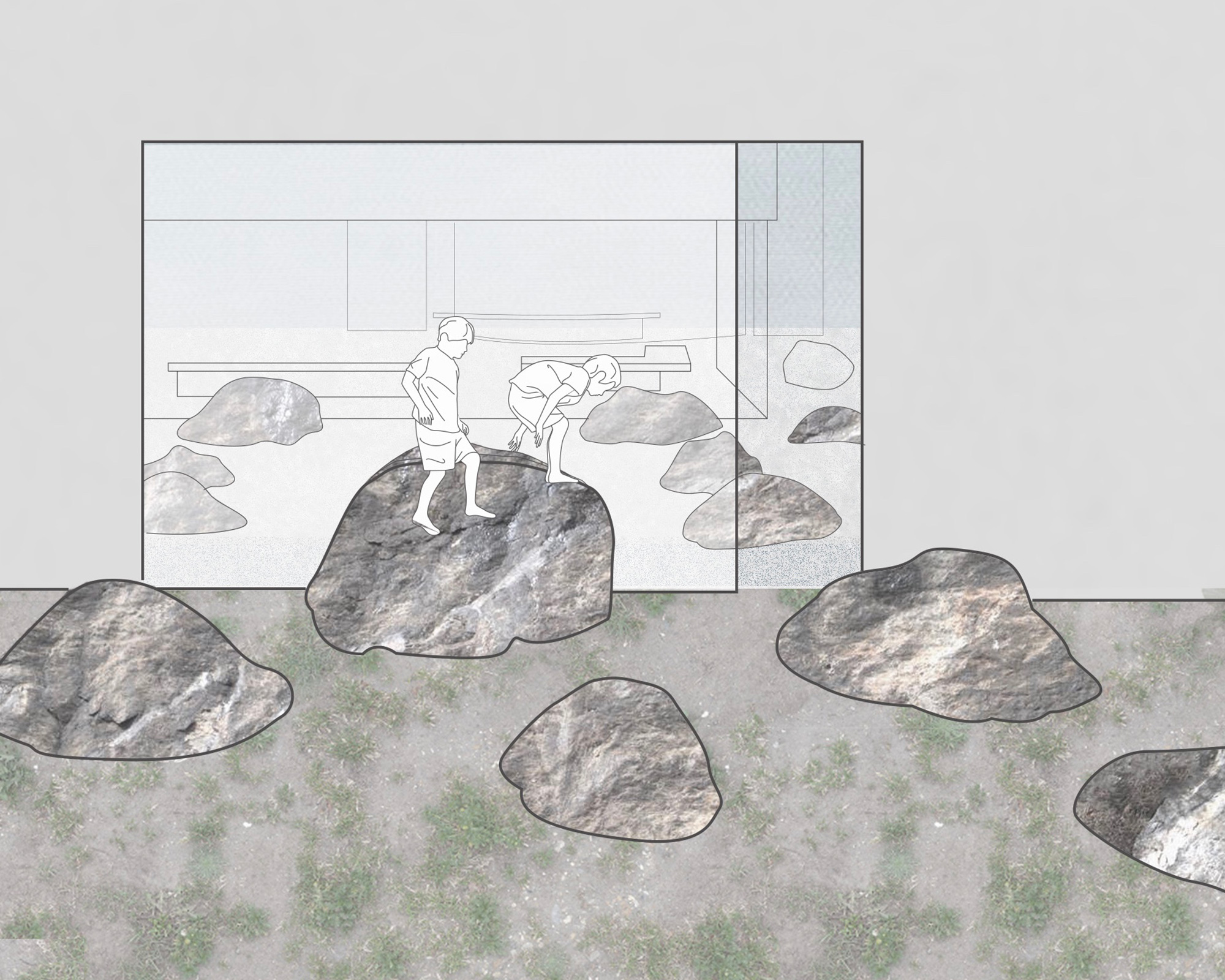

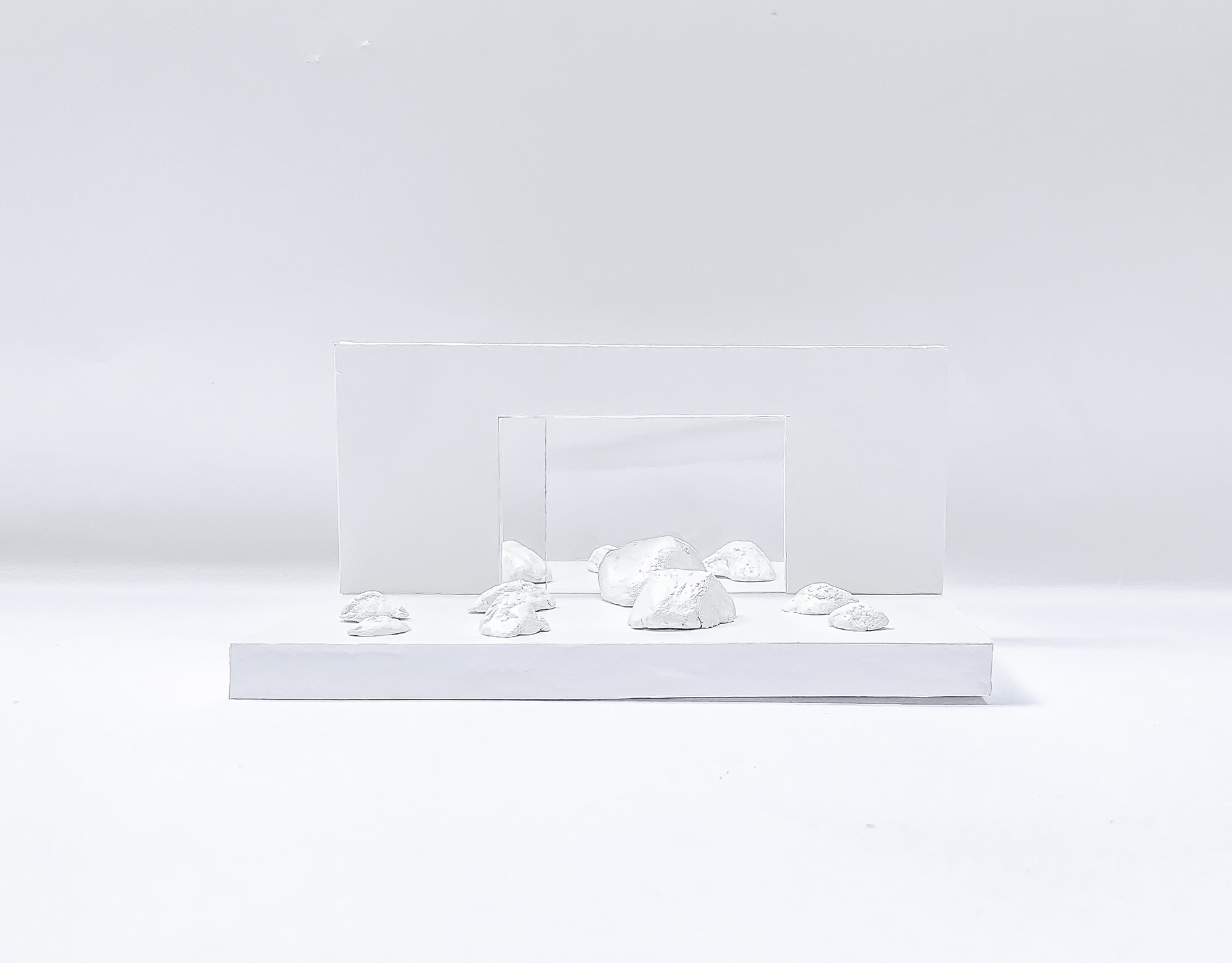

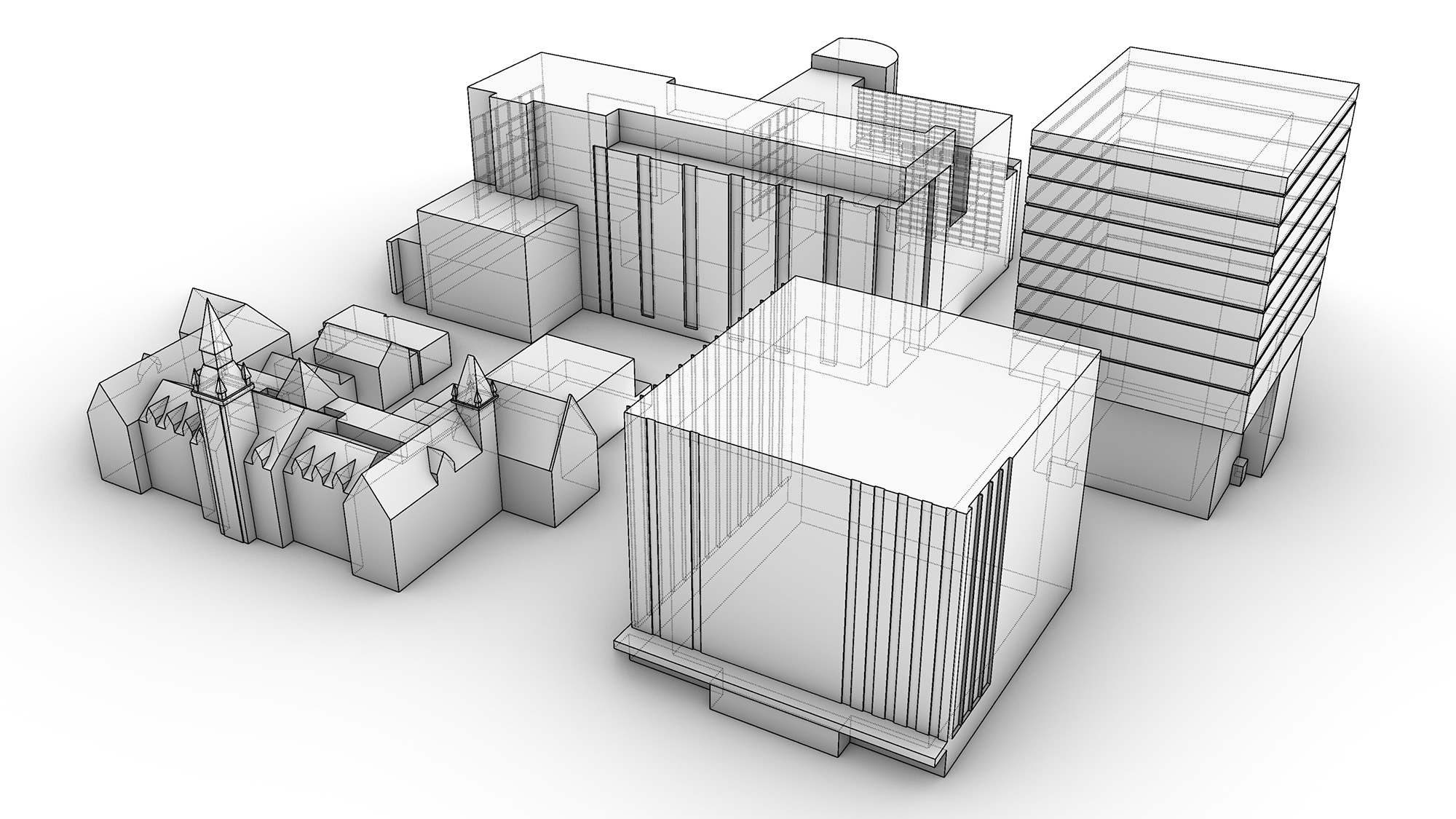

Phiffer's class isn't the only one learning to love Instagram's distance-learning capabilities. Assistant professor Petros Babasikas' undergraduate course, "History of Housing: Crisis, Visions, Commonplace" (ARC354) has been using the medium to its fullest. Groups of students have been posting elaborate photomosaics of their work — like this one, by Ozlem Bektas, Nicole Zohorsky, Patricia Prieto, Trumon Tse, Kenzie Burke, and Christopher Schaefer: