In your article “Decolonization, Reconciliation, and the Extra-Rational Potential of the Arts” written for ArtsEverywhere, you describe art as a method of “working toward a decolonized, Indigenized future other than through state sponsored and articulated processes of reconciliation.” Could you expand on this? In what ways can art contribute to decolonization?

Art allows us to have strange ideas. It’s a place where propositions can be made that can’t be made in politics or science. It’s a place where we can think differently. The Truth and Reconciliation Report (TRC) was published on behalf of the Canadian State. It was not an Indigenous-led process, and it is, we can generally say, a process that has been developed to ease of the mind of settler Canadians rather than address the trauma that is anchored in Indigenous communities. Art is a place where we can imagine a decolonized future not authored by the Canadian State, and it is important to hold the idea of decolonization in our minds going forward.

Why is it important for artists to take on this role?

If you are doing work or producing scholarship in Canada then you should be engaging with the political realities of this place. The production of art and the making of exhibitions is not neutral. It is important to realize how we perpetuate power relations in our work, and if you think there is something troubling about the way power is distributed in civic society then you should be doing something to counteract that.

What inspired your work in this area?

I grew up in northern Alberta on a farm, where there were a number of reserves close by, and my mom is of Ojibwe heritage. I have always thought a lot about what it means to be of mixed settler and Indigenous heritage. I don’t know how to look at culture in this country and not think about the ways that settler colonialism has impacted upon it.

You are the Director of No Reading After the Internet – a reading group for cultural texts. Could you describe the experience of reading an article aloud to a group? What are the outcomes of this activity?

No Reading After the Internet is an event where we read a cultural text aloud together. There are a couple reasons why it’s structured this way. The first is that it removes a barrier of entry. All you have to do is show up, and we encounter the text together. The other thing is that when people use their voice to read a text out loud, they are more apt to participate in the conversation that follows. One measure of success is whether everyone who came to an event spoke about the text. The nice thing about No Reading is that it de-emphasizes scholarship. We’re all encountering this text for the first time together. It’s much more improvisational than a class at school. It’s not about performing how smart you are; it’s about being curious, and being willing to think with other people. The conversations that come out of this process have been incredibly rich.

In July 2016, you were appointed the interim Artistic Director of Trinity Square Video (TSV). How has TSV contributed to the arts community in Toronto? What has been your vision going into this role?

Trinity Square has been around for over 45 years; it’s one of the oldest media arts, artist-run centres in the country. Its areas of activity revolve around production and presentation. For the creation of the work itself, we have production gear and post-production resources that our members can access. For the presentation of the work, we make exhibitions, coordinate screenings, host talks, and make publications. The production and presentation activities at Trinity Square are closely linked; there is reflexivity between the activities so that they inform one another.

John G. Hampton (MVS 2014), who was also a graduate of the MVS program, was at Trinity Square prior to me. I’m still in the process of realizing the exhibitions that he had put together. Going forward, I’ve been thinking about what it would mean to divest from white supremacy. Is there some way as an institution or as a structure that we can interrupt white supremacy through our work? I feel like the answer has to be yes, but I don’t know how exactly to do that yet, so I’m going to try and figure that out.

Do you have any advice for undergraduates pursuing a degree in Visual Studies from U of T?

I know art students are often encouraged to apply to open calls as a way to get their work seen. I would say that a better way to do this is to ask curators to do studio visits with you. As a curator, a studio visit is the basic unit of research. It is the equivalent to laboratory tests if you’re a scientist. So I would say find a curator that you respect, and ask them to come view your work and give you feedback.

What advice would you offer those considering the Master of Visual Studies in Curatorial Studies program?

Be as curious as possible. Go to as many shows as possible. Just writing a few sentences about every show you see to reflect on what you’ve seen and how you’re interpreting it is an incredible way to be critically present.

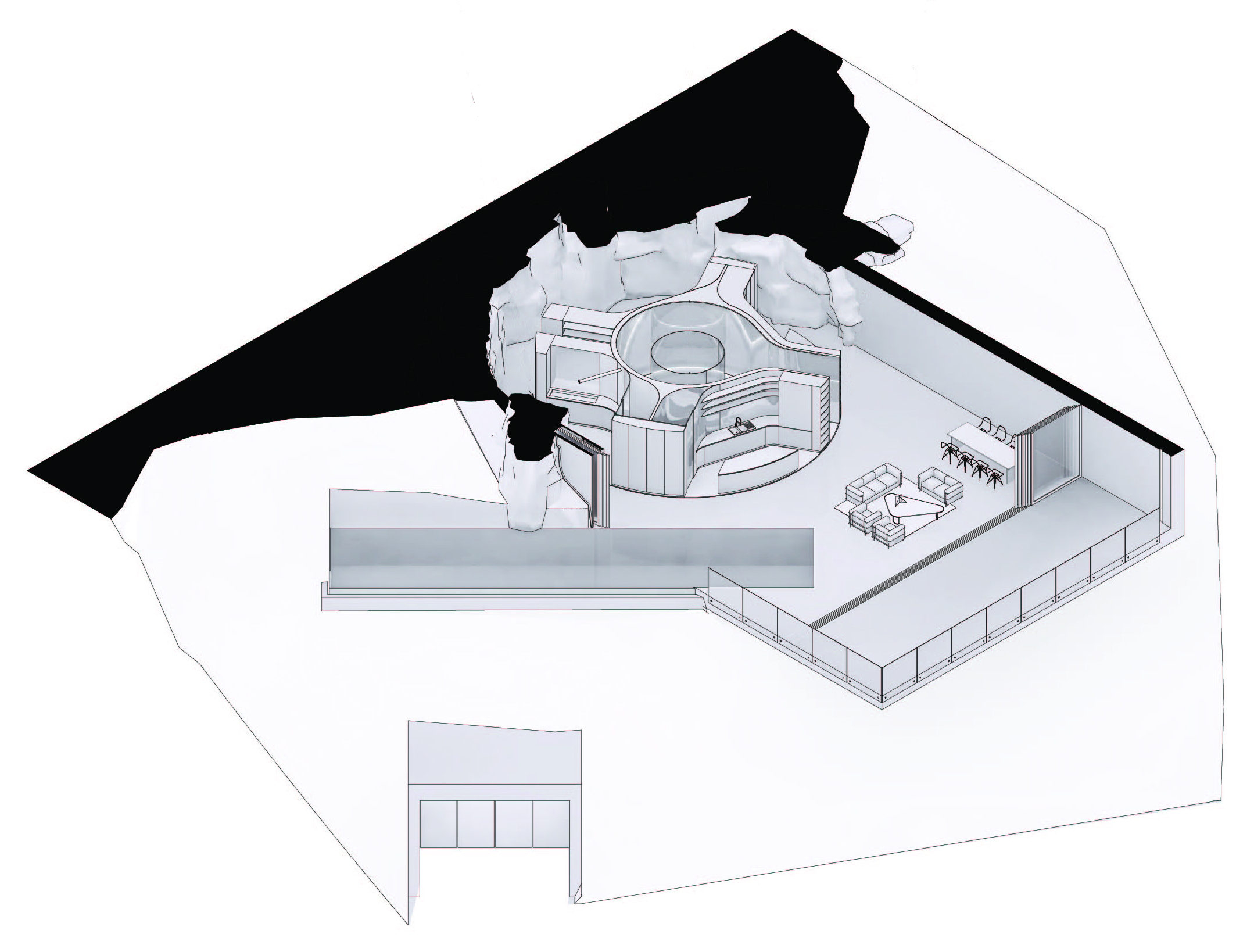

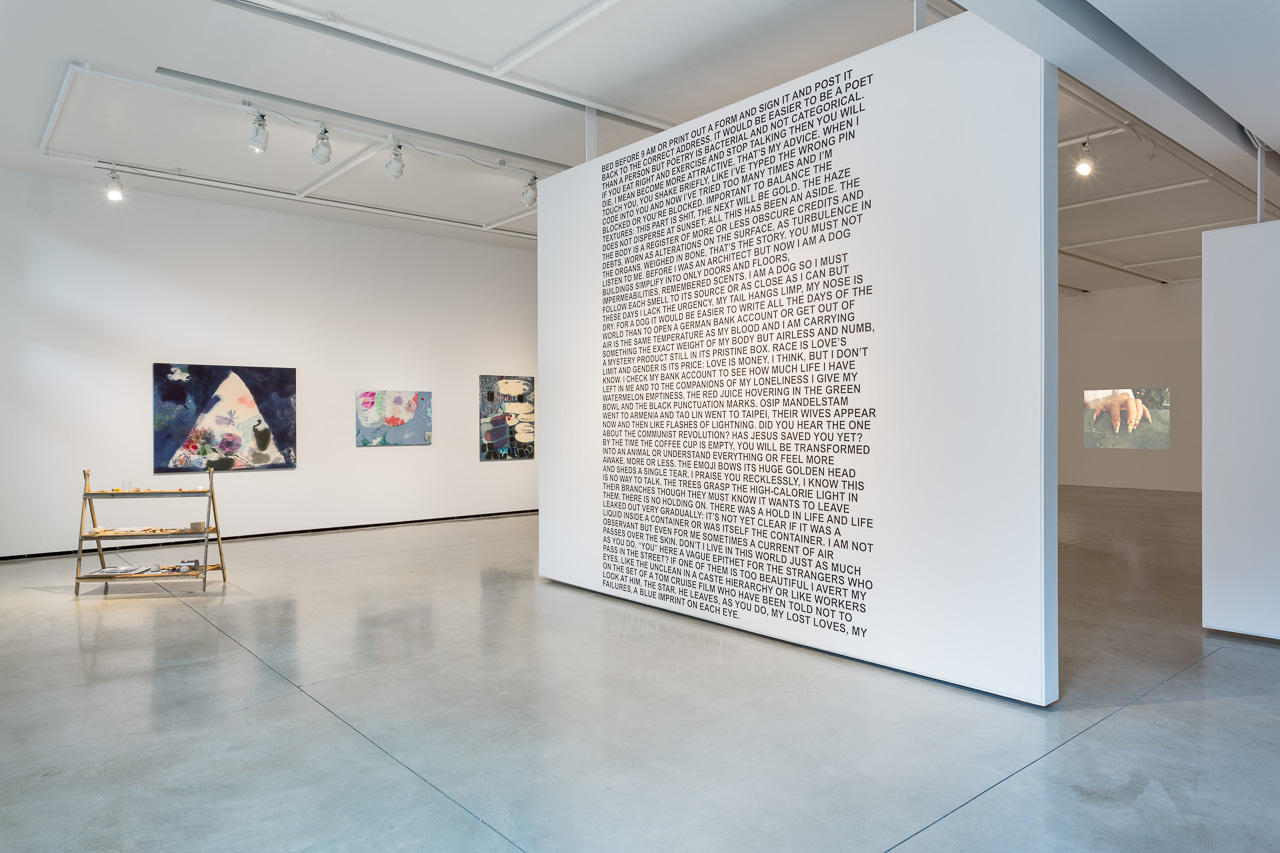

Photo, top: Image of exhibition The Fraud that Goes Under the Name of Love at the Audain Gallery. Photo by Blaine Campbell.