Shelley Long was born and raised in Calgary. Her father initially immigrated to Canada from south China to do his PhD, and ended up bringing his wife with him as well. (Photo provided by Long)

In terms of how I ended up where I am today, I graduated from U of T in 2015, then worked for five years in Vancouver in both private practice and as adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia, which I found a very rewarding experience. I love teaching, and I love being involved in both aspects of practice and academia.

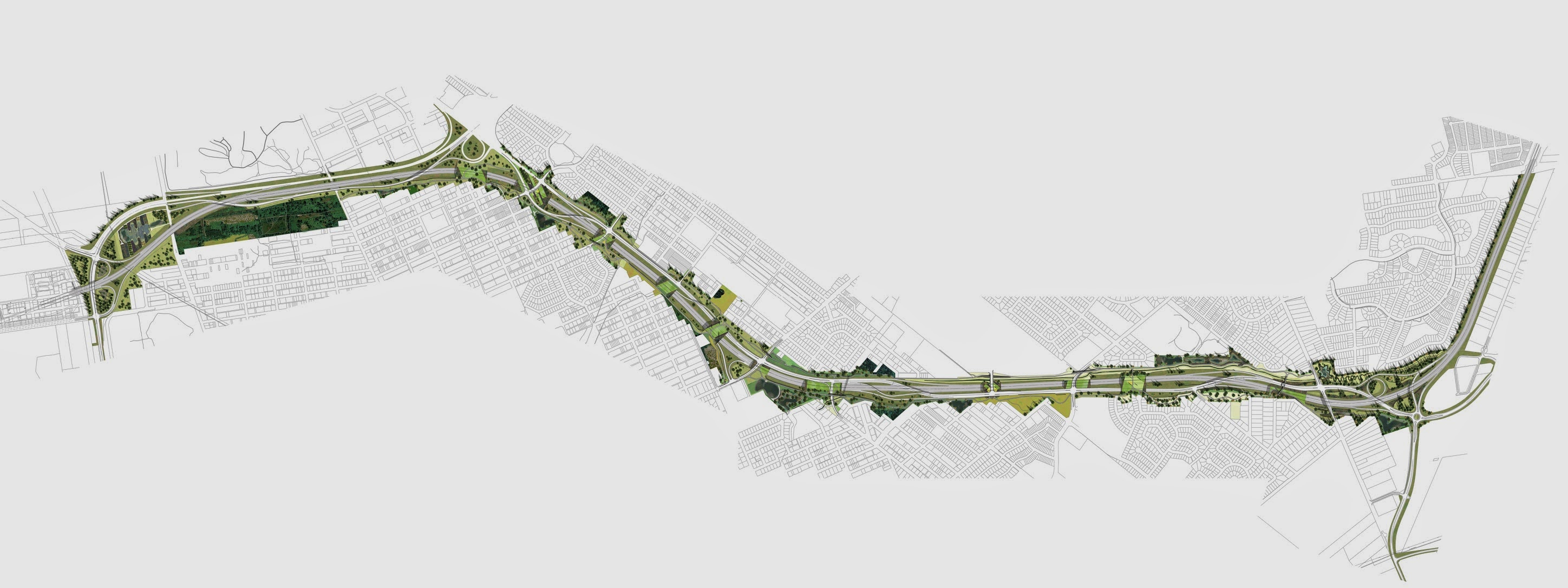

Four years ago, I moved to Rotterdam in the Netherlands, to join the team at West 8 Urban Design and Landscape Architecture. I had read [founder] Adriaan Geuze’s book when I was a student in Vancouver and actually attended his lecture when I was studying at the Daniels Faculty. I really wanted to work with him, so I guess I made that dream come true.

I’m a registered landscape architect in Ontario and B.C. and I do most of my work in Toronto, but also in the U.K. I don’t teach anymore because I don’t have time for that with this job.

Eha, you were recently appointed to the U of T’s governing council. Congratulations!

Naylor: Yes, thank you. It was announced in February. The council is essentially the University’s board of directors, and I’m one of the alumni governors. My role is, I believe, to champion the interests of the alumni, and to be part of the decision making for the University and its implications for alumni.

It doesn’t start until July, so I’m in training mode at the moment. There’s a learning curve for it. I have to give thanks to Doris, because she gave me a little push; she was very gentle about it, but she said you should do this. I’m looking forward to it. It is part of that transition from active practice to personal [endeavours].

How would you define that spectrum between active practice and personal pursuits?

Naylor: It’s the ability to have time to give back. I think I’ve been lucky in my professional life. I started in private practice and remained in private practice, and was part of a smaller, very progressive firm, led by Michael Hough and Jim Stansbury, in the 1980s. I ultimately became president of that firm. In 2009, we joined Dillon Consulting, a larger, multidisciplinary engineering firm.

These days, climate change, sustainability and protecting natural systems are paramount aspects of designing landscapes. How do they intersect with your work? And why are they important to you?

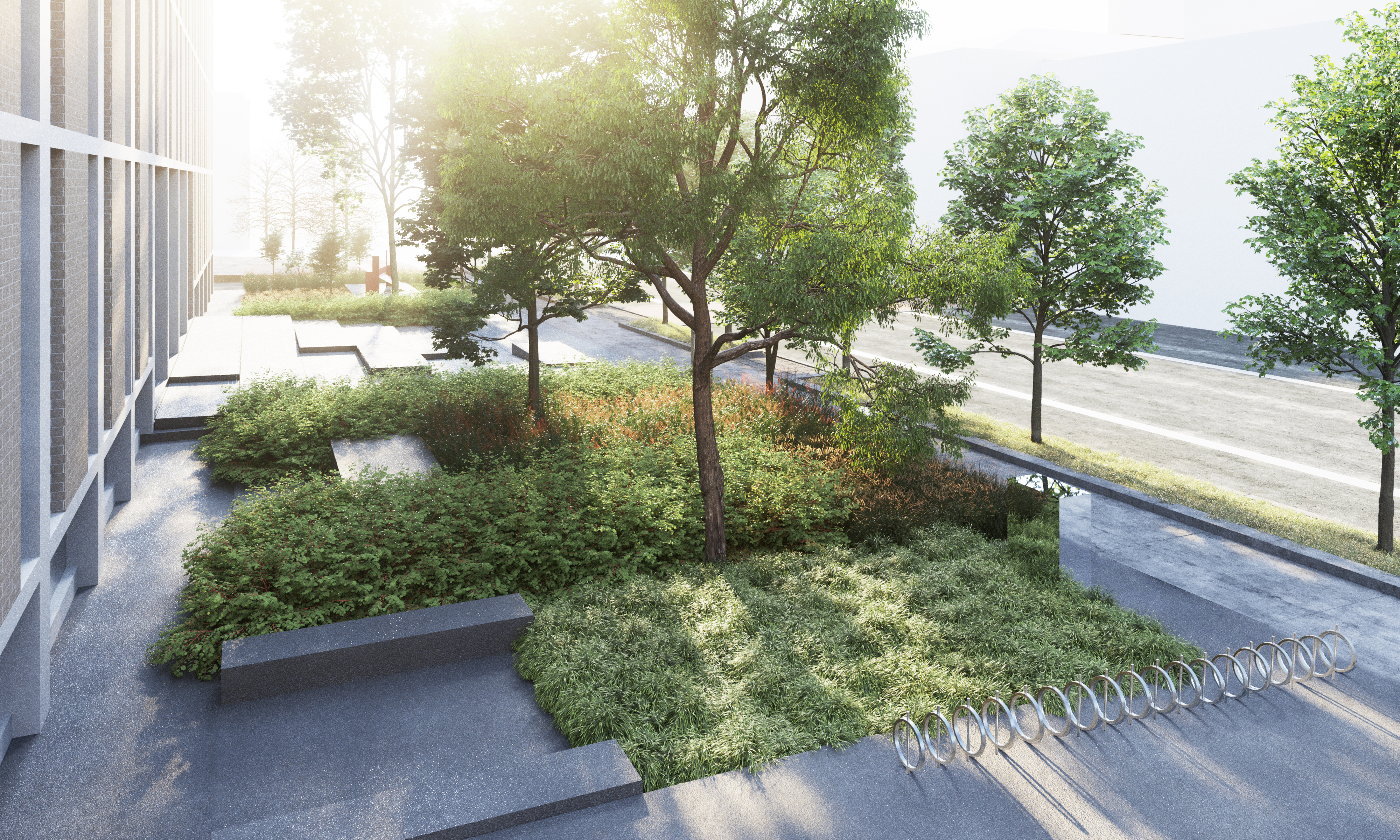

Long: As landscape architects, our role is to help connect people with natural systems. For my master’s studies, I had to choose between architecture or landscape architecture. I chose landscape architecture because it dealt with open systems and not closed ones. Landscapes only become better with time, whereas buildings start to fall apart the moment they’re complete. I thought, instead of making a fixed-point contribution, why not make something that gets better and more beautiful with time.

Naylor: I agree with Shelley. I think that is fundamentally not only why we choose to be landscape architects, but also why we continue to be landscape architects. About five years into my training, when I was first hired, I was quite frustrated. Not because of the work, but just because of the state of the business in those days. There wasn’t yet this kind of acceptance or understanding of how important it was to have a big picture of the environment. Landscape was relegated to tinkering around the edges.

To stay in this profession, you have to be able to embrace and articulate the larger vision of what it does. There have been environmental catastrophes, including climate change, that have made taking care of the physical environment and natural systems more understandable and urgent, whether they’re urban systems that provide natural environments or larger ecosystems.

Chee: These issues, as Eha said, have come to the fore because of events that are happening now. But that’s how we’ve always projected our work: adapting to climate change, being more sustainable, being more diverse in our work. And whatever we do, small or big, there’s a ripple effect, a downstream effect that becomes exponential.

Looking back on your careers now, is there a paradigm shift that you see within the profession when it comes to addressing these issues?

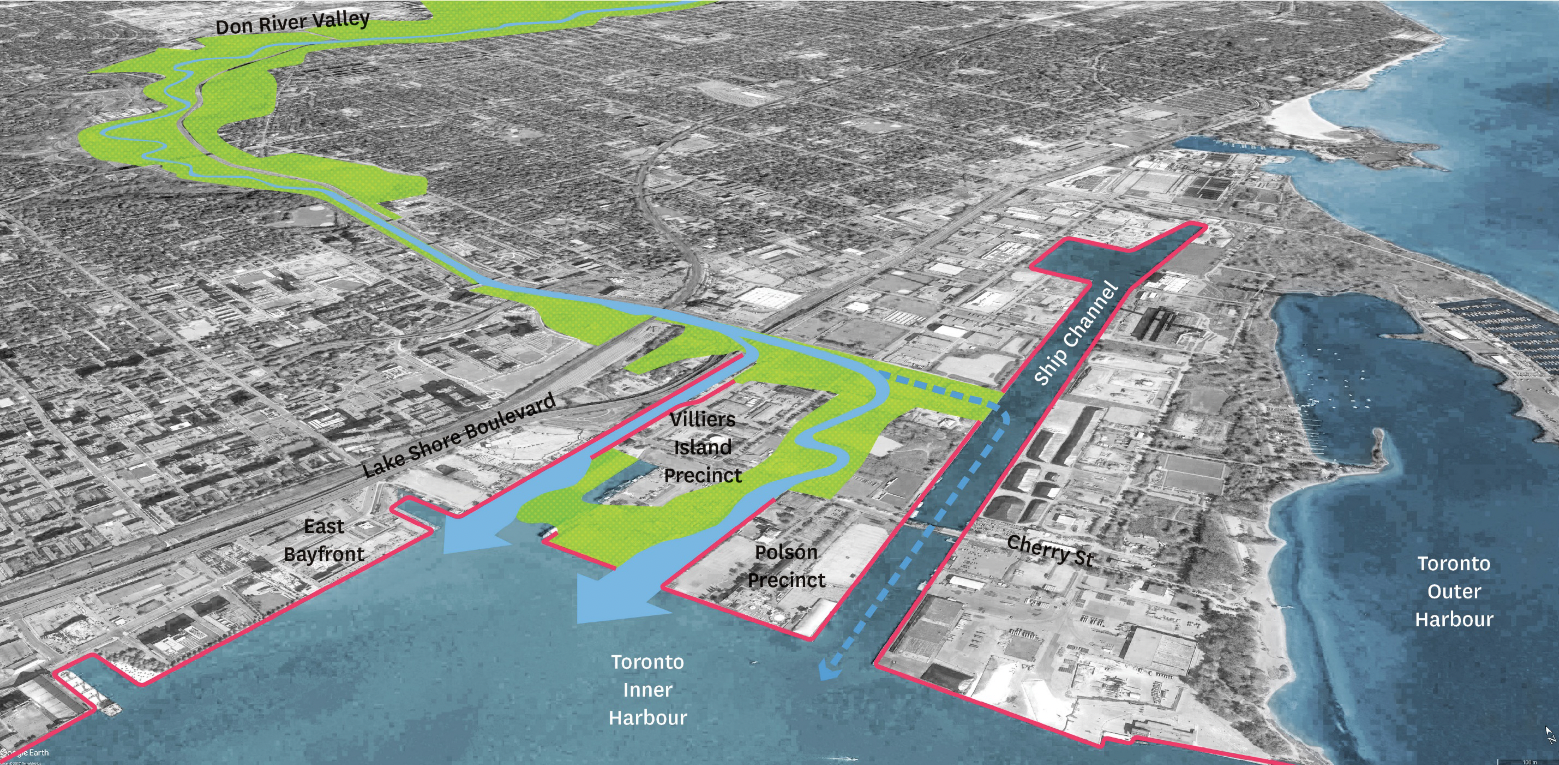

Naylor: Absolutely. In the 1980s, the concept of large-scale ecological restoration just wasn’t accepted. For example, I think it was probably in the early eighties that Michael Hough developed the strategy for the Lower Don Lands, and it involved recreating wetlands. He worked with a geomorphologist. And the work was certainly accepted, but it wasn’t widely accepted by other professionals.

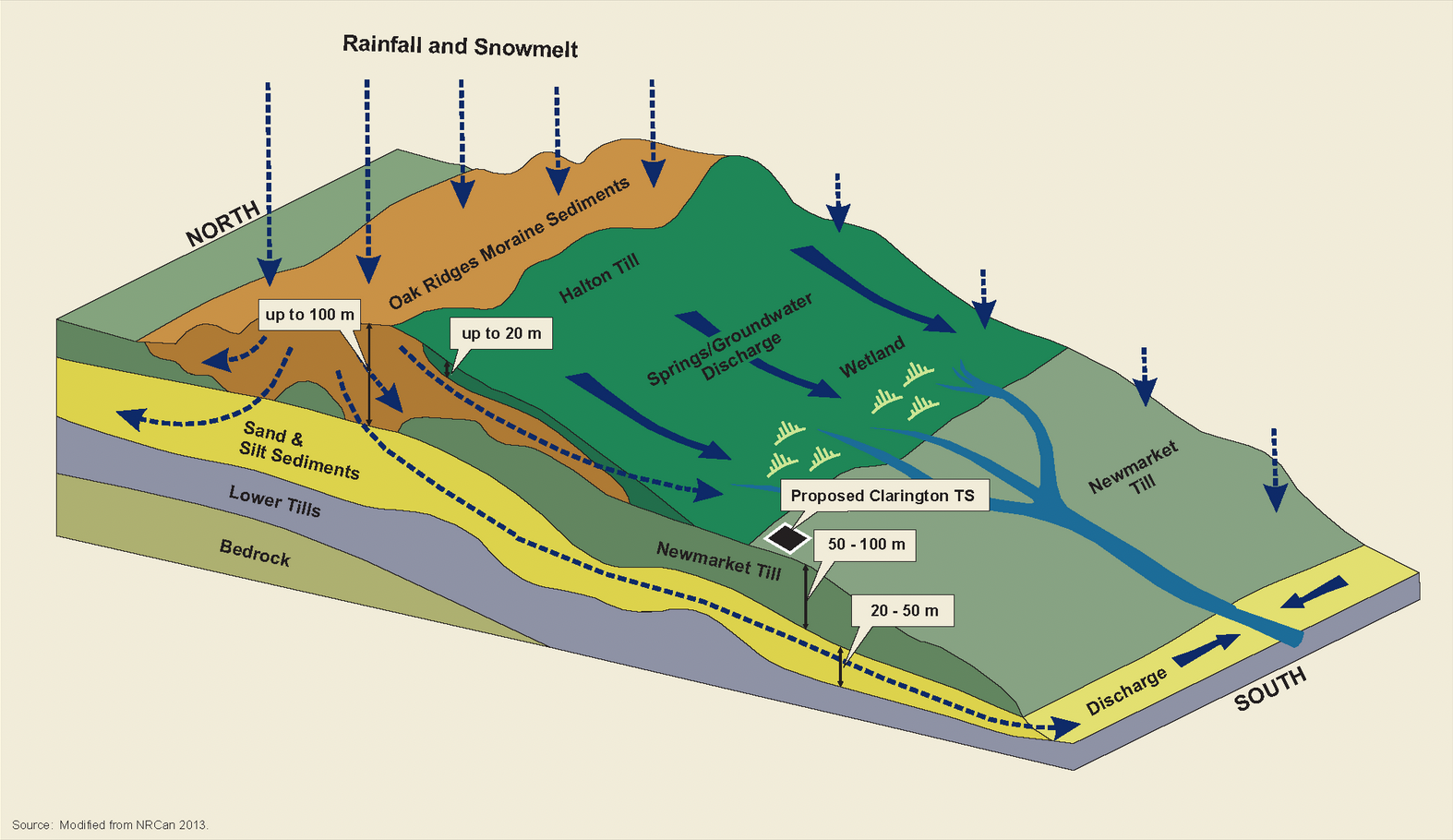

Stormwater management was still viewed as putting in a pipe; water was a nuisance to get rid of as quickly as possible. If you look at the work that’s happening now in the Port Lands, it is a huge change in thinking. The Don River [which is being renaturalized at its mouth] is becoming an enormous resource and the catalyst for a very important and high-quality renewal of the port.

That idea, I think, was initially outlandish for many and now it is mainstream thinking. But it’s probably taken 25 or 30 years for it to be accepted. I really admire the work that has been going on forever in the Netherlands. They’ve had to address these questions [of flooding and resiliency] for a long time, and have been able to explore those ideas physically.